Speculation about the next recession is rising as the following articles suggest.

-

- 7 Smart Market Thinkers Predict When The Next Recession Will Start. Forbes (May 9, 2018)

- Economists Think the Next U.S. Recession Could Begin in 2020, Wall Street Journal (May 20, 2018)

- What Will Cause the Next Recession? A Look at the 3 Most Likely Possibilities, New York Times (August 20, 2018)

- The next recession, The Economist (October 11, 2018)

We think this is a wasted effort. While the impact of recessions on stocks can be severe, timing them is not only quite difficult but can be counterproductive. Time is better spent on creating an asset allocation you can both (1) live with during downturns and (2) meets your goals.

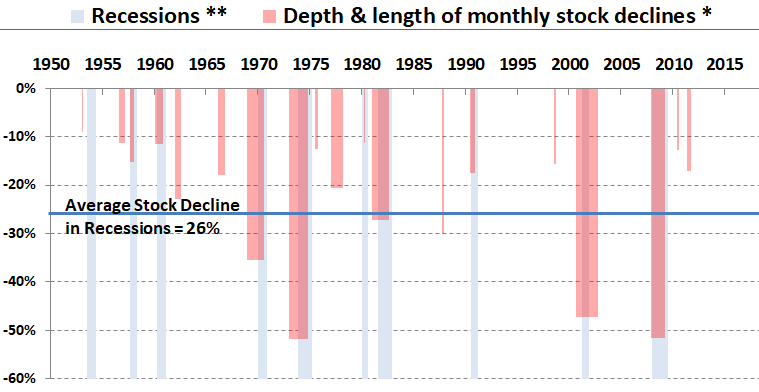

Stocks lose 26% on average during recessions. The chart below highlights S&P 500 index declines greater than 10% in red and recessions in blue since 1950. The effect of inflation is excluded so real purchasing power comparisons can be made over time.

Since 1950, there were ten recessions or about one in every 7 years. They ranged in length from 6 to 16 months and, on average, lasted 11 months. The chart also includes stock declines not associated with recessions. They appear as red bars standing alone without a blue background and are shorter than those associated with recessions.

* S&P 500 declines greater than 10% are calculated from month-end prices, including dividend returns but excluding inflation. Excluding inflation provides a fair purchasing power comparison over time. Annual inflation ranged from -2.1% to 14.8% so including it would distort the real impact of declines. Compared to declines calculated from end-of-day prices, many setbacks of 10% or more are lost from the absence of extremes within a month. But the main conclusion remains the same: the average recession decline is nearly the same. However, the number of stock declines 10% or more doubles with daily prices. Yardeni Research, Inc. tracks these declines using daily prices. ** The NBER defines recessions as ” a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales.” Sources: National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank, Morningstar.

-

- Stock declines have a loose relationship with the start of recessions. Stocks start falling more than 6 months, on average, before recessions start. But declines can start as early as 13 months before a recession (1969-70) and, in the rare case, stocks can fail to decline 10%. Case in point, during the short-lived January to July 1980 recession stocks rose 6.1% in January. In the chart only blue shading appears, the red highlight indicating a 10% decline or more is missing.

- Predicted recessions do not always materialize. Accurate forecasting is hard. In an interview on All Things Considered in July 2010, an expert on business cycles said, “…when we look at the backdrop of the business cycle for the coming decade, it virtually dictates more frequent recessions than most people can remember.” For the record, no recession has yet occurred in the eight years since. In that time the S&P 500 compounded at over 15% enabling a $1.00 investment to grow to $3.24, a costly mistake for those heeding this forecast.

- Waiting for recessions to be announced is not an easy road to profits. If you sense a significant slowdown in the economy but wait for an official announcement, you may miss much of the decline. The exact recession dates are determined by NBER with a delay. For example, the December 2007 peak was announced 12 months later on December 1, 2008. The decline during that period was 39%. Waiting for an official announcement would have missed that decline. Announcements can be as fast as 6 months into a recession and as slow as 21 months.

- Buying during a recession creates the same set of timing challenges. Stocks typically sniff a recovery before the recession’s end, but it varies. On average stocks hit bottom four months before recessions end. It can be as early as 7 months (1973-75) but sometimes stocks continue falling after the recession’s end. They fell another 29% over 10 months after the 2001 official recession end. Even if you somehow sense a bottom you will have to buy when the economy looks bleakest.

A better course of action: choose a stock/bond mix you can stick with when the next recession hits.

Overestimating your tolerance for declines can damage your wealth during a recession. Selling stocks after they have declined and then getting back in when “the coast is clear” is likely to detract from performance. The coast appears clear typically after prices are higher. And higher prices means the full market return is not earned over time.

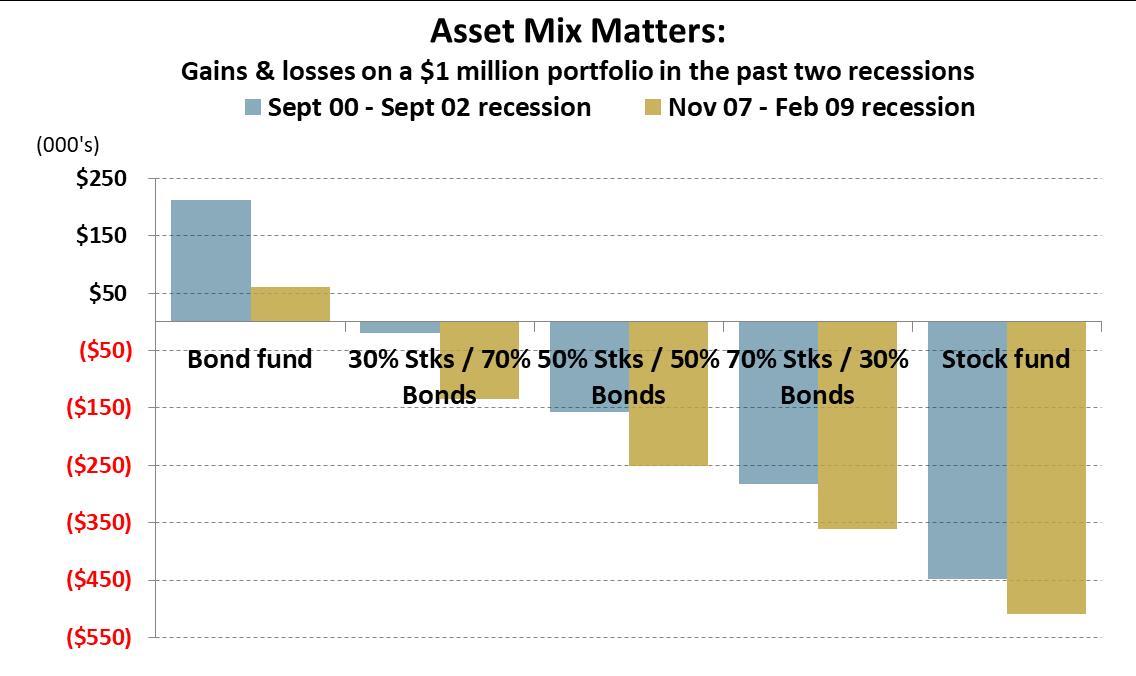

The impact of declines on a few portfolio stock and bond mixes during the last two recessions is shown in the graph below. The far right of the chart is a portfolio of 100% stocks, the Vanguard 500 (stock) Index fund. It declined by 45% and 51% in the early 00’s and during the global financial crisis of 07-09, respectively. On a $1 million portfolio, that’s $450,000 and $510,000. The urge to get out of the market and preserve what was left proved irresistible for many.

Stock & bond portfolios rebalanced annually. Transaction and advisor fees excluded. Bonds = Vanguard Total Bond Market Index Investor fund. Stocks = Vanguard 500 Index Admiral fund. Source: Morningstar.

Stocks may now constitute a greater proportion of your portfolio due to the bull market over the past ten years. If so, now is the time to think about what you can stomach in a recession induced bear market. In the graph, this means moving to the left and moderating stock declines with bonds. Essentially this is rebalancing. It is one method of managing risk which helps take the emotion out of buying and selling through market ups and downs.

This blog entry is distributed for educational purposes and should not be considered investment, financial, or tax advice. Investment decisions should be based on your personal financial situation. Statements of future expectations, estimates or projections, and other forward-looking statements are based on available information believed to be reliable, but the accuracy of such information cannot be guaranteed. These statements are based on assumptions that may involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties. Past performance is not indicative of future results and no representation is made that any stated results will be replicated. Indexes are not available for direct investment. Their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio.

Links to third-party websites are provided as a convenience and do not imply an affiliation, endorsement, approval, verification or monitoring by Granite Hill Capital Management, LLC of any information contained therein. The terms, conditions and privacy policy of linked third-party sites may differ from those of this website.