After crossing into Venezuela from the Colombian border town of Cúcuta on our recent vacation, we proceeded to a lodge an hour away. The stream of evening car headlights coming toward us on the two-lane road numbered in the hundreds. Why so many on a Saturday night?

I soon discovered that much of the traffic consisted of gas smugglers. The subsidized price of gas in Venezuela works out to 4.3 cents per gallon at the official exchange rate, the lowest in the world.

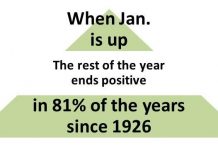

![Total sale = [2.78 bolivars / 39.77 liters] * [$1 / 6.3 bolivars] * [3.77 gallons / 1 liter] = 4.3 cents / gallon at the official exchange rate of 6.3 bolivars per dollar, an artificially strong rate reserved for critical imports. At another official, less favorable exchange rate of $1 / 50 bolivars, gas costs a half-penny per gallon.](https://granitehillcapital.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Venezuela-080.jpg)

Total sale = [2.78 bolivars / 39.77 liters] * [$1 / 6.3 bolivars] * [3.77 gallons / 1 liter] = 4.3 cents / gallon at the official exchange rate of 6.3 bolivars per dollar, an artificially strong rate reserved for critical imports.

At another official, less favorable exchange rate of $1 / 50 bolivars, gas costs a half-penny per gallon.

Smuggling gas is easy income. With brick-and-mortar gas stations selling at $2.18 per gallon across the border in Cúcuta, one can simply siphon it out and net $20 for 10 gallons at today’s low prices. Given low wages in Venezuela, it is an attractive pursuit. Indeed, at our first lodge the owner said it was difficult to find workers because smuggling paid so well. Returning to Cúcuta for our outbound flight in the light of day, we saw many vendors of smuggled gasoline.

Lots of gas is smuggled. An estimated 10 million gallons slips across the border to vendors, or pimpineros, each month at various crossings, according to Quarterly Americas.

Pimpineros’ livelihoods depend on the disparity between subsidized Venezuelan gas prices and the highly taxed Colombian ones. In towns like Cúcuta, poverty and violence have pushed entire neighborhoods to become “pueblos bomba”—“pump towns”—whose economies are based entirely on the smuggling, home storage and selling of pimpinas (five-gallon—19-liter—containers) of hydrocarbon-based products. Thousands of low-income Colombian families spend days and nights in their improvised street shacks, pouring gas through handmade funnels into their clients’ tanks.

Steps taken to prevent smuggling are creative but ineffective.

-

Spot checks of gas tanks occur as vehicles pass the border. Drivers are allowed only half a tank upon entering Colombia. Any more and it is siphoned off by soldiers. However, smugglers have a workaround for the half-tank rule: jigger the fuel gauge to stick at a half tank or less.

-

Drivers may only fill their tanks once every other day. Cars have electronic devices attached to their windshields to enforce this. Even so, strong demand creates block-long lines at some stations near the border.

-

Border crossings are limited and now closed from 10 p.m. to 5 a.m. every day to clamp down on not only gas but subsidized food. We found out our driver can only take 12 trips across the border per month.

-

A “Contraband” warning in the form a semi-truck hauling a tank of gasoline parked at a checkpoint. To smuggle such tank-load quantities of gasoline would require high-level connections and many payoffs. Apparently someone did not remain quiet.

Raising gas prices appears to be the easy solution. However, memories of 1989, when prices were raised and hundreds of people died in riots protesting increased bus fares, remain. The Wall Street Journal article, Almost-Free Gas Comes at a High Cost, discusses this as well as other subsidy effects:

The fuel subsidy helps explain why Venezuela finds itself in an unusual situation: A major oil exporter that is chronically short of cash. Venezuela’s budget deficit reached 12% of gross domestic product last year, according to Moody’s Investors Service, worse than in troubled euro-zone economies. A lack of dollars on the street — because the government hoards them — has led to shortages of imported goods, even as price controls discourage Venezuelans from producing many items locally.

The cash crunch means state oil giant Petroleos de Venezuela SA invests too little to fully develop its potential. Crude-oil output is down by a quarter from 1998, the year before Mr. Chavez came to power.

At the same time, Venezuelans’ use of gasoline and other refined products rose 65% in 2011 from 1998, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Compared with next-door Colombia, where market prices prevail, Venezuelans used nearly seven times as much gasoline per capita.

That plus Venezuela’s crumbling refinery network leaves the country with the largest crude oil reserves in the world needing to import gasoline.

Its energy subsidies, the International Energy Agency calculates, cost Venezuela $27 billion in 2011, a figure that reflects cash left on the table by not selling fuel at market prices. That was equivalent to 8.6% of gross domestic product. Government spending on health was 3.25% of GDP that year, and on education, 5.1%.

Raising gas prices would be an affront. Venezuelan’s love their old cars from the 1970s, imported during the days of high oil prices from the OPEC embargos. While we did not see any land yachts, old Chevy Caprices and Dodge Darts were common and an old Nova would turn up on occasion. Our guide mentioned if a V-6 died, it might be replaced with a V-8. They like their cars powerful and fast.

Economic distortions from centrally planned prices are pervasive. Some are obvious and others intricate:

-

Essential products can be difficult to find, as this AP story explained:

First milk, butter, coffee and cornmeal ran short. Now Venezuela is running out of the most basic of necessities — toilet paper.

Blaming political opponents for the shortfall, as it does for other shortages, the embattled socialist government says it will import 50 million rolls to boost supplies.

“This is the last straw,” said Manuel Fagundes, a shopper hunting for tissue in downtown Caracas. “I’m 71 years old and this is the first time I’ve seen this.”

Economists say Venezuela’s shortages stem from price controls meant to make basic goods available to the poorest parts of society and the government’s controls on foreign currency.

“State-controlled prices — prices that are set below market-clearing price — always result in shortages. The shortage problem will only get worse, as it did over the years in the Soviet Union,” said Steve Hanke, professor of economics at Johns Hopkins University.

President Nicolas Maduro, who was selected by the dying Hugo Chavez to carry on his “Bolivarian revolution,” claims that anti-government forces, including the private sector, are causing the shortages in an effort to destabilize the country.

-

Cars qualify as inflation hedges, as the Washington Post noted. When we passed a few car dealerships in Colombia on the way to the border, our guide told us to take notice of their full showrooms. In Venezuela, the few times we passed dealerships, their showrooms were completely empty.

The value of used vehicles has doubled in the past year, dealers say, because virtually no new cars are entering the country and local assembly plants have been paralyzed.

Consider: A bare-bones 2012 Toyota Corolla is worth nearly $40,000 in Caracas today, shooting up 100 percent in value since January — and that’s the price in U.S. dollars, unrelated to the runaway inflation that plagues the local bolivar.

Venezuelan car dealers say many of the vehicles are being bought and sold to outrun inflation pressures, not to get around town.

-

Cashing-in on a vacation. Traveling out of the country provides an illegal opportunity to profit from the government’s fixed exchange rates. Because bolivars buy so little outside the country, the government provides dollars at favorable rates both in cash and on a credit card. Simply spend fewer of these dollars out of the country and sell the rest at black market rates back in Venezuela. A Bloomberg article, How Venezuelan Used ‘Scrape’ to Make Six Times Her Salary, describes it.

The scheme, known as “raspao” or “big scrape,” is booming in Venezuela as a decade of currency limits causes a dollar shortage that is fueling the fastest inflation in the region and a scarcity of staple products including rice and toilet paper. From Miami to Madrid, travelers use the raspao to undermine socialist President Nicolas Maduro’s rules on dollar purchases.

“The raspao business has become more attractive today than ever because the spread between the black-market dollar and the official rate is greater than ever,” said Henkel Garcia, director of Caracas-based research company Econometrica. “The socialist system has created a subsidy that allows you to travel practically for free.”

It took 29 bolivars to buy a dollar on the black market rate when this article was written a year and a half ago. On our visit it took five times more, or 180 bolivars, to buy a dollar.

-

Using the black market to obtain essential imports. The black market is active in Cúcuta as NPR’s All Things Considered, Hopping From Venezuela To Colombia To Evade Currency Controls, recounts.

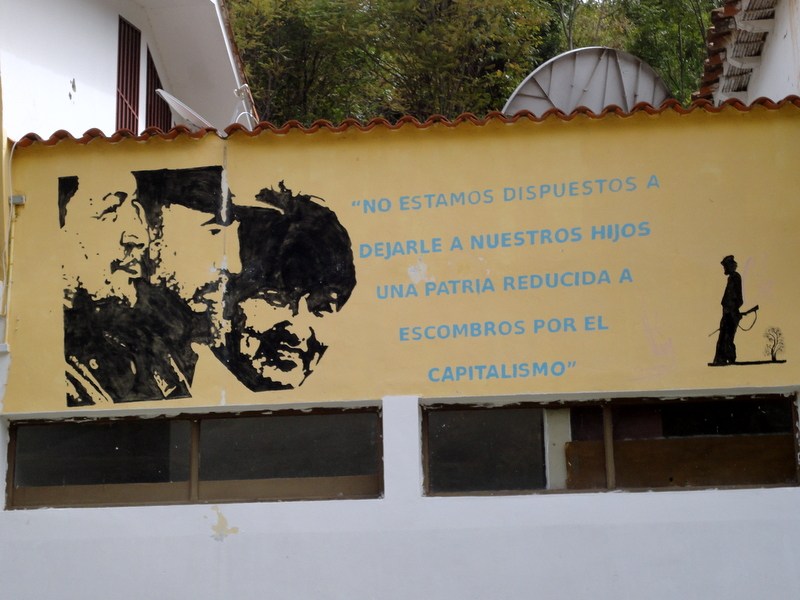

These economic distortions are rooted in Hugo Chavez’s socialistic revolution. Murals tell the story:

Images of Hugo Chavez, Fidel Castro, and Evo Morales (President of Bolivia) in San Jose.

“We are not willing to leave to our children a country reduced to rubble by capitalism.”

Add one more to the list.

“So who still believes markets don’t work? Apparently it is only the North Koreans, the Cubans and the active managers.” – Rex Sinquefield, Active vs. Passive Management.

Sinquefield’s paper, written in 1995 and before Hugo Chavez became President in 1999, captures well the fallacy of centrally planned prices versus free markets:

The 20th century has produced two grand experiments that bear directly on the question “do markets work?” One experiment took place on the geopolitical stage and the other in the halls of academia.

The intellectual origin for the role of free markets and the price system goes back to Adam Smith. He was the first to offer a comprehensive statement that markets work and that a free market is the best way for a social order to allocate resources. In his Wealth of Nations he shows that countries with such a system prosper, while those without do not.

Friedrich Hayek extended the work of Smith and tried to provide insight as to why and how the free market system works. The key idea is that the price system is a mechanism for communicating information. The knowledge that is relevant for producing any good or service is never possessed by a single individual or a single group. Rather, it is dispersed among many market participants. The price system acts to spread this knowledge and coordinate the actions of individuals.

But there is another side to this story. The ideas advanced by Adam Smith were not only ideas. An abiding faith in the power of man’s reason was augmented by the success in the physical sciences. From the middle of the 19th century to the 20th century there was a growing belief among some intellectuals that man’s success in the physical world could be applied to the social order as well.

This was in part the intellectual genesis of the first grand experiment referred to earlier. In 1917, much of the world began organizing itself—forcibly and brutally—on a belief that centrally administered prices and planning [are] superior to a system based on free market prices. Surely, a group of bright people by intelligent design and management could increase social welfare better than a system that was undesigned and unmanaged. So, much of the world was subjected to socialism. But deprived of a mechanism to gather and disseminate the widely dispersed information on how to deploy society’s resources for the production of goods and services, deprived of free market prices, it was inevitable that socialist countries would collapse. In retrospect, it would be impossible to design a more controlled experiment at the geopolitical level than the one we witnessed for most of this century. The verdict is in. The socialists have thrown in the towel. And in some of these countries, the new emergent hero is none other than Adam Smith.

Hugo Chavez missed the absurdity of centrally planned prices, but what about active fund managers? Sinquefield argued that stock prices reflect the combined knowledge of all participants in the market and therefore, trying to pick under- or over-priced stocks or bonds because you think you know something that is not in the market price is a fool’s game. Yet active fund managers believe they can determine the right stock or bond price just as a central planner can determine the right product price. The evidence of just how difficult this is to achieve in practice is abundant and hard to refute. For one example, see 99.93% of Active Stock Funds Underperform.

If you want to explore changing your investing approach away from a foundation similar to that of central planning, give us a call. This alternative, using index and index-like funds and ETF’s, acknowledges the power of the market and provides low costs and tax efficiency to boot.

Links to third-party websites are provided as a convenience and do not imply an affiliation, endorsement, approval, verification or monitoring by Granite Hill Capital Management, LLC of any information contained therein. The terms, conditions and privacy policy of linked third-party sites may differ from those of this website.

This blog entry is distributed for educational purposes and should not be considered investment, financial, or tax advice. Investment decisions should be based on your personal financial situation. Statements of future expectations, estimates or projections, and other forward-looking statements are based on available information believed to be reliable, but the accuracy of such information cannot be guaranteed. These statements are based on assumptions that may involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties. Past performance is not indicative of future results and no representation is made that any stated results will be replicated. Indexes are not available for direct investment. Their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio.

Links to third-party websites are provided as a convenience and do not imply an affiliation, endorsement, approval, verification or monitoring by Granite Hill Capital Management, LLC of any information contained therein. The terms, conditions and privacy policy of linked third-party sites may differ from those of this website.