Right now it’s hard to find an investment that makes money. Safe bonds earn paltry interest and banks pay next to nothing on deposits. Stocks, while risky, at least pay dividends. You may be wondering whether it is time to boost your allocation to stocks. The answer is a resounding “maybe.” Before leaping, here are a few things to consider.

Stocks are more volatile than bonds:

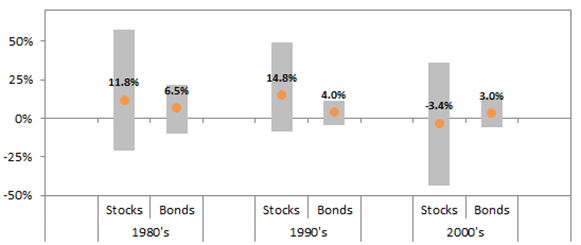

No surprise here. The best and worst 12-month periods across three decades are illustrated by the gray bars below. (We’ll get to what those orange dots mean in just a second.)

What is readily seen is that the length of each decade’s stock bar is considerably longer than that same decade’s bond bar. That means that stocks routinely experienced higher highs and lower lows … more volatility. In fact, the range of best and worst performances was between double to quadruple more for stocks than for bonds. That’s a lot of bounce in those bars.

U.S. Stock and Bond Volatility and Performance

Inflation-adjusted:compounded rate of return noted by the orange dot. Large company stocks are represented by the S&P500 and bonds by the Barclay’s Capital Intermediate US Government Bond index. Dividends, interest and capital gains reinvested.

Takeaways:

- Stocks are a wild ride — When you invest in stocks, expect similar wider swings to continue, for two reasons: in the event of bankruptcy, bondholders’ claims get paid before stockholders, and bonds have a maturity date whereas stocks do not.

- Smooth the ride with bonds –Combine stocks and bonds in proportions you can stick with. Your discomfort with stock holdings in 2008–2009 can be a starting guide to your mix of stocks and bonds: more discomfort, more bonds. (For further discussion see our white paper, Begin Your Journey with Stock Bond Decisions.)

- Stick with your mix – Accurately and consistently figuring out the next best or worst 12 month performance period is impossible, so once you’ve selected an appropriate stock/bond mix for your needs, be prepared to stick with it over time.

Why bother with stocks to begin with? Because …

Higher risk typically provides higher returns.

This is where those orange dots above come in. They reveal that stocks outperformed bonds in the 1980s and 1990s by 5.3% and 10.8%, respectively. Typical is the operative word. Large company US stocks fell from 2000 to 2009, as most are painfully aware. But, so far in 2010-2011, stocks are again up 3% higher than bonds, which happens to be the same premium found across the entire period, 1980-2011.

Takeaways:

- Be patient – Patience is needed to obtain the higher expected returns of stocks.

- Spread your risk around – Even with patience, expected returns don’t mean guaranteed returns, so diversify among different classes of stocks and also internationally to spread risks.

- Have a safety net – Make sure you have enough bonds (or similar reliable income sources) to supplement social security and possibly annuity income if you are retired and withdrawing from your accounts. This will carry you through the inevitable stock slumps so you don’t have to sell at distressed levels.

Find the right mix for you.

So should you own more or fewer stocks? While it would be nice if there were a universal “right” stock/bond balance, as usual, reality is much fuzzier.

First, there’s uncertainty inherent to the market:

Let us admit the obvious: Unless we possess a crystal ball, we cannot [estimate future returns]… with a great degree of accuracy. The best that we can do is to come up with what financial economists call an “expected return,”… — William J. Bernstein, The Investor’s Manifesto: Preparing for Prosperity, Armageddon, and Everything in Between

Second, there are your own, personal circumstances guiding how much risk and expected return make sense for you. For some, it can mean consulting with an investment advisor to help you sort through the factors involved. For many, it might mean erring on the side of caution. For all of us, the most important thing is to arrive at a balance that, once selected, removes second-guessing. It’s those second guesses that cost you time, money and emotional stress. Who needs that?

Copyright © 2012, Granite Hill Capital Management, LLC.

This blog entry is distributed for educational purposes and should not be considered investment, financial, or tax advice. Investment decisions should be based on your personal financial situation. Statements of future expectations, estimates or projections, and other forward-looking statements are based on available information believed to be reliable, but the accuracy of such information cannot be guaranteed. These statements are based on assumptions that may involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties. Past performance is not indicative of future results and no representation is made that any stated results will be replicated. Indexes are not available for direct investment. Their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio.

Links to third-party websites are provided as a convenience and do not imply an affiliation, endorsement, approval, verification or monitoring by Granite Hill Capital Management, LLC of any information contained therein. The terms, conditions and privacy policy of linked third-party sites may differ from those of this website.